Let there be light: meet the engineers tackling light and dark

Light and dark are two of the most powerful conflicting natural resources. A new wave of engineers are attempting to intermingle the two.

Words Ellen Himelfarb

A legendary lighting designer once said: ‘Let there be light.’

What he proceeded to do was separate the light from darkness. Believe what you want about this designer, but the light was good – so good, people have been trying to mimic its natural quality ever since.

The results have been mixed. Some of the more successful expressions of light were created in an effort to connect spiritually with this great designer. Yet the most poignant examples embrace the duality of light and darkness in a tightrope walk between the two. Take the Pantheon, that magnificent arched rotunda built at the centre of Rome 2,000 years ago as a place of worship.

At the height of its coffered dome, a perfect circular oculus invites in moving shafts of natural light that, says lighting innovator Rogier van der Heide, ‘can only appear because there is also darkness in that same building’. In other words, the quality of light comes from its interplay with its foil.

In his atmospheric lamps for Philips, spotlighting concepts for museums across Europe and his coining of the word ‘darkitecture’, van der Heide makes a case for incorporating darkness in lighting design. What sounds counterintuitive – a reverence for darkness in a field focused on illumination – is rather a celebration of contrast, imagination and passion in lighting that is only now coming to interiors in a big way. Hallelujah.

‘The job of any lighting designer is composing darkness and brightness in order to create a space that’s comfortable, attractive and even inspiring and energising,’ says van der Heide. ‘There’s no light without shadow. Without contrast it’s dull.’

Van der Heide is almost evangelical in his mission to challenge our longest held assumptions about lighting. The solitary pendant light, a dramatic gesture forever considered a style statement, ‘doesn’t do anything,’ he says.

‘At least if it was directed toward the wall, it would create interest and give us a pleasant visual. But no – we don’t think about it.’

The same goes for downlights. ‘In places where we relax,’ he says, ‘light always comes from the ceiling. But the moment you put light below eye level, it becomes intimate and cosy.’

As if answering a message from on high, some European lighting brands have garnered notice recently for their spotlights, uplights and hybrid systems that diffuse light and cast deep shadows around a space. German manufacturer ERCO subverts traditional tracklighting with its wide-beam Skim lights that throw broad swathes of ambient light around a room.

And Belgian designer Kreon recently released a line of adjustable LED projector-lights that disperse interesting patterns of light, and recessed wall and floor LED luminaires that give off gentle

washes of light. Its lights are not just effective but affective, because the ultimate goal of a lighting designer, says van der Heide, is to offer a sense of comfort. ‘It’s giving people the ability to feel excited about a space, giving a space the right mood at the right time – you walk in and feel great.’

What constitutes ‘good’ lighting varies between professions and indeed within them. Yet scholars and scientists agree with creatives that variations in light can increase wellbeing. Glaring lights are a strain on the eyes. Uniform, institutional light can hamper the recovery of a patient, or the learning curve of a school-age child. Lighting that fluctuates with our circadian rhythms helps us feel fitter: alert and sleepy at exactly the right times. It’s just less quantifiable. You can’t measure good lighting in lumens per square metre just like you can’t measure happiness.

Like scientists, though, the most effective lighting designers should always be asking, ‘Why?’ Why must lighting be a top-down affair? Why does ‘efficient’ have to mean ‘bright’? Why can’t kitchens be lit like the rest of the home?

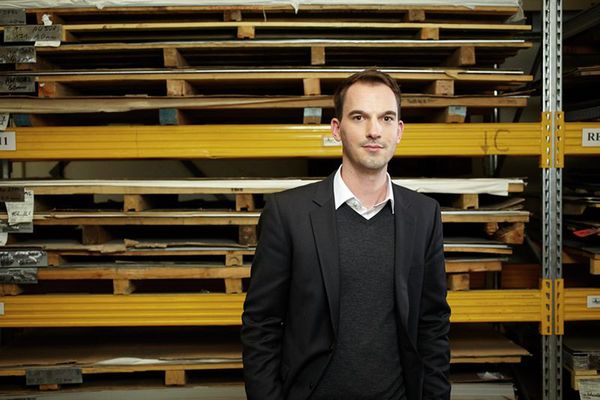

These questions – particularly the last one – have preoccupied Lars Dinter for years. Dinter joined Gaggenau as a lighting strategist after more than a decade designing lighting, during which time he produced amber-glow pendants, geometric glare-free sconces, ultra-slim tube lights… everything but your average lamp.

When he turned his focus to kitchen lighting, he maintained his ‘big-thinking’ approach. He looked to architecture, art and the high design of Norway-based designer Daniel Rybakken, who incorporates stimulating, life-affirming light effects into the surface make-up of his home furnishings.

Luxury fashion boutiques, museums and French patisseries are a big influence, too, places that appeal to human emotion with highquality, high-concept lighting. In spaces like these, light and shadow interact with the architecture to enhance and romanticise the product on show – which is what they should do in a contemporary kitchen, rather than make the mechanics disappear.