Pottery 2.0: how Oliver van Herpt is reinventing an ancient craft

We meet the 27-year-old Dutch designer who’s using 3D printing to change the way ceramics are made

Words Lucy Brook

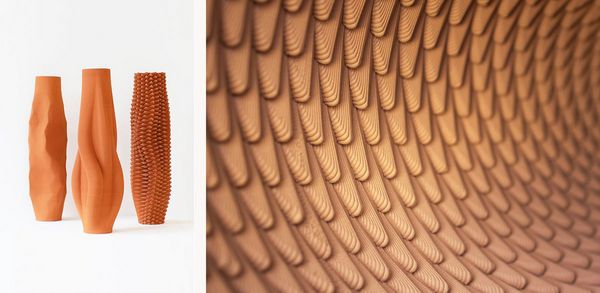

It’s difficult to define Dutch designer Olivier van Herpt. Is he a sculptor or a ceramicist? An artist or a digital innovator? A creator of objects or the maker of machines? The 27-year-old, whose organic, textured clay vessels are brought to life using 3D printing technology, says that he is, in essence, a problem-solver.

‘My creative process starts with a problem: what is a thing that can’t be made?’ he says from his studio in Eindhoven, about an hour south-east of Rotterdam. Van Herpt finds inspiration in the gaps between his imagination and a physical product, gaps that, traditionally, couldn’t be bridged. Then, he conjures up technology – such as the 3D printing and digital fabrication methods he’s developed after years of trial and error – to turn his dreams into a reality. ‘So I’m somehow not a maker of things,’ he says, ‘but a maker of devices that let me, and others, make things.’

Van Herpt’s ‘things’ are objects of great beauty. His fluid, futuristic shapes are crafted from clay, beeswax and even paraffin, and have catapulted him onto the global art stage. Since he started working with his 3D printer five years ago, he’s been in hot demand.

In 2017, he collaborated with Swedish retailer COS, producing a series of clay vessels inspired by the brand’s Spring/Summer collection, and Wallpaper* Handmade, for which he teamed up with designer Tijmen Smeulders to create pieces informed by elements of religious architecture. He’s held solo exhibitions, partnered with a sound designer to turn sound vibrations into shapes using his 3D printer, and created a bronze portrait of the 2016 Chemistry Nobel Prize winner, Ben Feringa.

His 3D printing technique is unique. By pushing the limits of existing 3D printing technologies, van Herpt has created bespoke machines that produce larger forms and work with materials beyond the conventional plastics.

‘3D printing is accelerating in manufacturing,’ he says. ‘Increased reliability, repeatability and better quality control are the types of things I’m excited about at the moment. I do like talking to dreamers, but now a lot of conversations I have are with engineers and production people and this is especially exciting.’

Van Herpt grew up in a creative household, ‘playing at the foot of an easel and a drafting desk’. His father, an architect, and his mother, a teacher, encouraged his endless drawing and disassembling. ‘I’ve always been curious as to how things worked,’ he says.

He studied graphic design and has always worked within the digital space. He started building his 3D printing machine in 2012, which ‘looking back,’ he says, ‘was an insane thing to attempt’, and was struck by the idea of working with ancient materials and new technology.

‘I’ve always found myself on the cusp of the analogue and the digital,’ he says. ‘The digitisation of the world is something that’s surrounded me my whole life. I’m from a generation that can’t imagine life without the internet.’

But he has always admired noble materials, such as ceramics, stone and glass. ‘To make things with them feels almost like an honour,’ he says. ‘One has to hone one’s craft before working with stone. Mistakes in stone are expensive and permanent. 3D printing afforded me an opportunity to work with these materials. Pottery and ceramics are also crafts that have been honed over millennia. There’s a real connection with the past when you work in ceramics or pottery.’

‘ There’s a real connection with the past when you work with ceramics ’

There seems to have been a surge in the popularity of ceramics and pottery courses lately. Does he think we’re craving more hands-on, tactile experiences in our very digital world?

‘Definitely. Most of our experiences come to us via screens, not the real world. We yearn to feel the interaction with the physical. This explains not only a global resurgence of interest in pottery, but also a new-found love for baking and other activities where touch is a key element.’

Having found a way to fuse ancient tradition with pioneering technology, van Herpt says he hopes to continue creating work that is both functional and beautiful.

‘The world is filled with superfluous items,’ he says. ‘To be able to make objects that are useful, fulfil a purpose and are beautiful is what I’m always trying to do.’